Epilepsy and Alcohol: Risks, Effects, and Safe Guidelines

Learn how alcohol impacts epilepsy, seizure risk, medication interactions, withdrawal effects, and safe drinking guidelines for better seizure control.

When talking about Alcohol and epilepsy, the way drinking alcohol influences seizure disorders, the first question is simple: does a drink make seizures more likely? The short answer is yes, but the details matter. Alcohol can lower the seizure threshold, interfere with medication levels, and cause withdrawal‑related seizures when you stop drinking. Understanding these links helps you decide whether to enjoy a glass of wine or skip it altogether. Below, we’ll unpack the main factors that shape this relationship and give you practical pointers you can use right now.

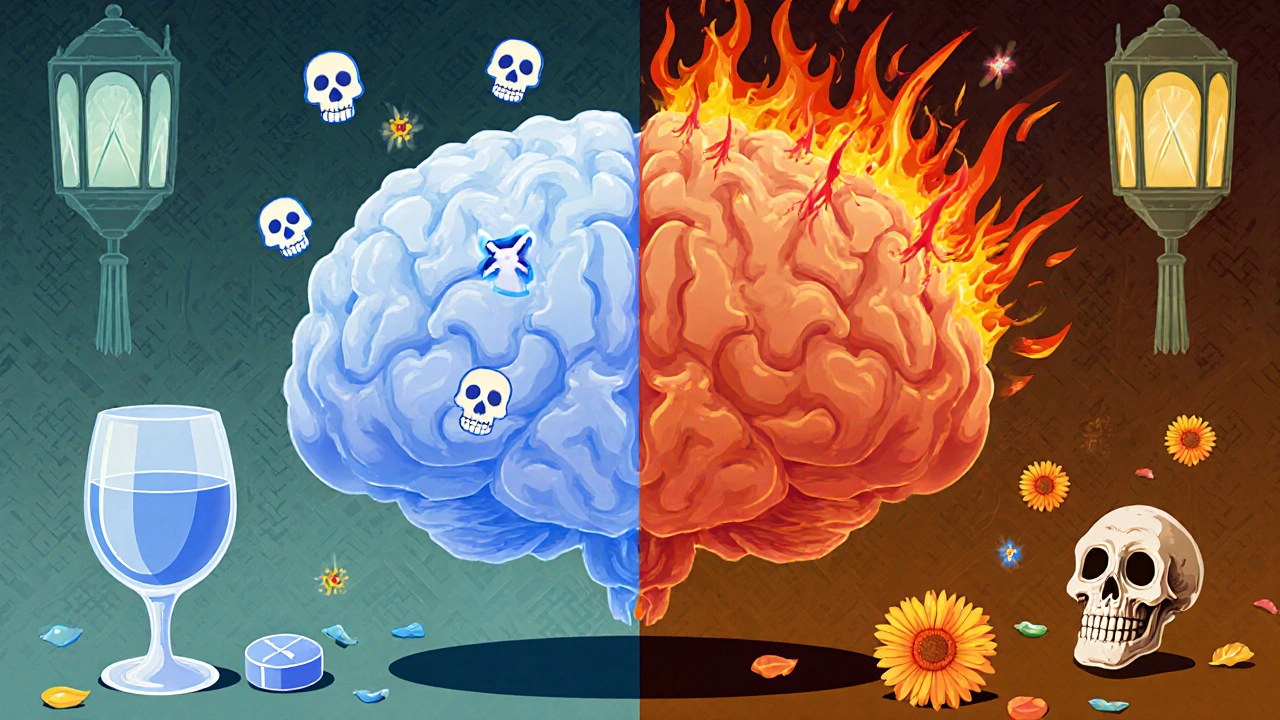

One of the core concepts is the seizure threshold, the level of brain excitability required to trigger a seizure. Alcohol acts as a depressant, but paradoxically it can make the brain more excitable once the blood alcohol level drops. This rebound effect means that a night of drinking may be safe while you’re intoxicated, yet the hours after you sober up are high‑risk for seizures. Another piece of the puzzle is how alcohol interacts with antiepileptic drugs, medications used to control seizures. Many of these drugs are metabolized by the liver, the same organ that processes alcohol. Drinking can either speed up drug clearance, lowering effectiveness, or inhibit metabolism, raising toxic levels. The result is a delicate balance: a few drinks might make your medication less reliable, while heavy drinking can push concentrations into dangerous territory.

Beyond the immediate effects, Epilepsy, a chronic neurological condition characterized by recurrent seizures itself shapes how you should approach alcohol. People with well‑controlled epilepsy on stable medication may tolerate occasional light drinking, but anyone with frequent seizures, medication changes, or comorbid conditions should be cautious. The risk isn’t uniform; it depends on seizure type, dosage, and personal tolerance. For instance, focal seizures that start in one brain region might be less sensitive to alcohol than generalized tonic‑clonic seizures, which involve the whole brain. Knowing your seizure pattern lets you gauge how much risk a drink adds.

Then there’s the challenge of alcohol withdrawal, the set of symptoms that appear after stopping or reducing alcohol intake. Withdrawal can trigger seizures on its own, especially in people with a history of epilepsy. Even a brief interruption after regular drinking can spike seizure risk, sometimes more than the drinking episode itself. This creates a paradox: stopping alcohol abruptly may be riskier than continuing moderate use for some patients. The safest route is a gradual taper under medical supervision, particularly if you decide to quit.

Putting these pieces together, we see several semantic connections: Alcohol and epilepsy encompasses the interaction of alcohol consumption with seizure thresholds; it requires careful management of antiepileptic drug levels; and it is influenced by the underlying condition of epilepsy as well as potential withdrawal effects. Understanding each link helps you make informed choices, whether you’re planning a social event, reviewing your medication regimen, or considering cutting alcohol out entirely.

Below you’ll find a collection of articles that dive deeper into each of these topics—from how specific drugs like carbamazepine react to alcohol, to practical tips for reducing seizure risk during holidays, to strategies for safe tapering. Use the guides to match the information to your personal situation, and feel confident making decisions that protect your brain while still enjoying life.

Learn how alcohol impacts epilepsy, seizure risk, medication interactions, withdrawal effects, and safe drinking guidelines for better seizure control.