Back in 2015, the FDA replaced the old pregnancy letter categories-A, B, C, D, X-with something far more useful. If you’re still looking for that little letter on a drug label and wondering what it means, you’re looking at outdated information. Today, every prescription drug approved after June 30, 2015, uses a detailed narrative format to explain risks during pregnancy and breastfeeding. And if you’re a patient, a nurse, a pharmacist, or even a doctor, you need to know how to read it.

Why the Old Letter System Failed

For over 35 years, doctors and patients relied on those simple letters: A, B, C, D, X. It seemed easy. A meant safe. X meant don’t take it. But here’s the problem: most drugs fell into C. About 70% of them. That didn’t tell you anything. Was it risky? Maybe. Was it safe? Maybe. The letter didn’t say. And patients? They heard ‘C’ and assumed it was dangerous-even if the actual risk was tiny. A 2017 FDA study found that 68% of people misread the letter system as a safety grade, not a risk summary. That’s why the system was scrapped.The New System: Three Sections You Must Know

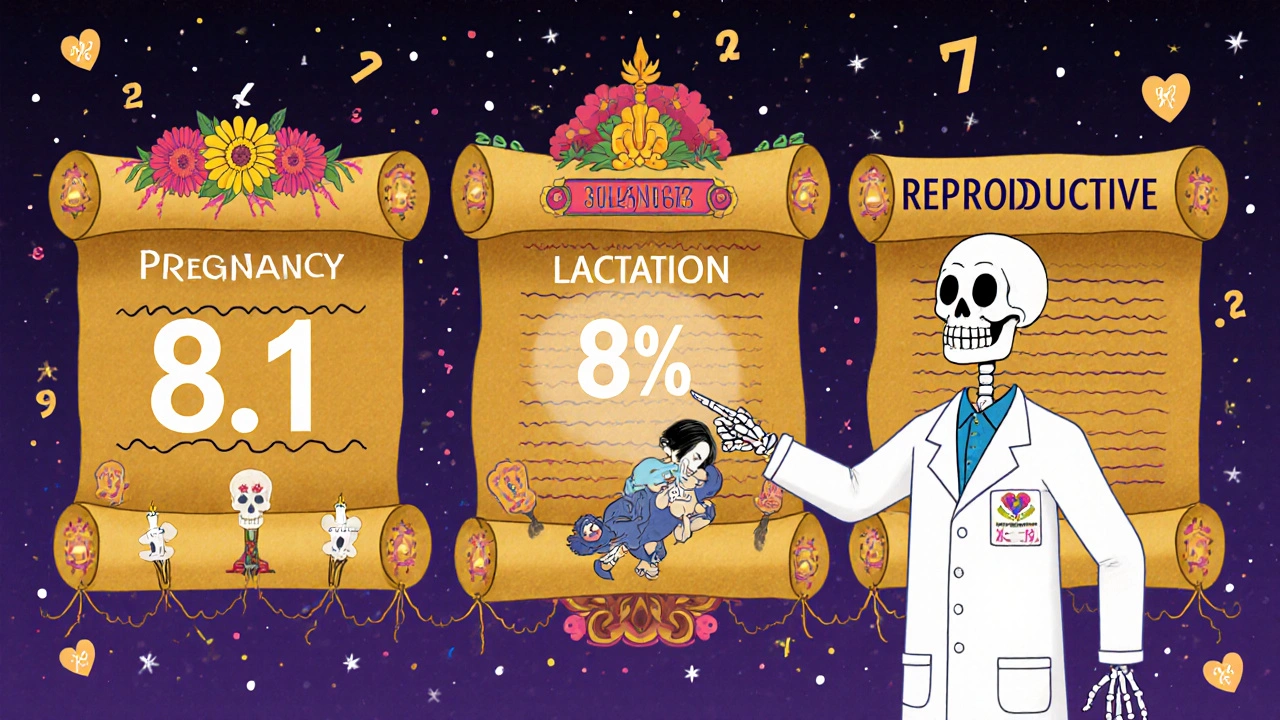

Today, every drug label has a section called Use in Specific Populations. Inside that section, there are three subsections: Pregnancy (8.1), Lactation (8.2), and Females and Males of Reproductive Potential (8.3). Each one follows the same structure: Risk Summary, Clinical Considerations, and Data. Let’s break them down.Pregnancy (8.1): What You Need to Know

The Risk Summary doesn’t say ‘safe’ or ‘dangerous.’ It tells you the actual numbers. For example: ‘The background risk of major birth defects in the U.S. general population is 2-4%. Exposure to this drug during the first trimester was associated with a 1.5-fold increased risk of neural tube defects.’ That means if the normal risk is 3%, this drug might raise it to 4.5%. That’s not the same as saying ‘it causes birth defects.’ It’s a small increase, and it’s clear. The Clinical Considerations section tells you what to do. It might say: ‘Monitor fetal growth every 4 weeks after 20 weeks gestation.’ Or: ‘Avoid use in the third trimester due to risk of neonatal withdrawal.’ This is where you find actionable advice-not just theory. The Data section is the evidence behind the claims. It lists studies: ‘Prospective cohort of 1,200 pregnancies, 95% confidence interval 1.2-1.9.’ That tells you how solid the data is. If a study only had 15 women, the FDA won’t let them claim anything strong. This section helps you judge if the risk is real or just a guess.Lactation (8.2): Breastfeeding and Medications

This is where the new system shines. The old system barely mentioned breastfeeding. Now, every drug label must say how much of the drug gets into breast milk. You’ll see phrases like: ‘Infant exposure is estimated at 8% of the maternal weight-adjusted dose.’ That’s a number you can use. If it’s under 10%, most experts consider it low risk. If it’s over 20%, you need to think harder. It also tells you what to watch for in the baby: ‘Rare reports of drowsiness and poor feeding in breastfed infants.’ Not ‘don’t breastfeed.’ Just ‘watch for this.’ And if there’s a known issue-like with certain antidepressants or opioids-it’ll say: ‘Avoid use if infant has G6PD deficiency.’ That’s specific. That’s helpful.Females and Males of Reproductive Potential (8.3)

This part isn’t just for women. It’s for anyone who can get someone pregnant-or get pregnant. It tells you: ‘Pregnancy testing required before starting treatment.’ Or: ‘Use two forms of contraception with a combined failure rate of less than 1%.’ It might even say: ‘Discontinue drug 30 days before attempting pregnancy.’ This section is often overlooked, but it’s critical for planning.How to Use This Info in Real Life

You won’t find a quick cheat sheet on the label. But here’s how to make it work:- Look for the Risk Summary first. What’s the baseline risk? What’s the increase? Is it a doubling? A 10% rise? Context matters.

- Check the Clinical Considerations. What should you do? Monitor? Avoid? Adjust dose? This is your action plan.

- Read the Data section only if you need to dig deeper. Most of the time, the summary and clinical advice are enough.

- For breastfeeding, focus on the infant exposure percentage. Under 10%? Usually fine. Over 20%? Talk to a specialist.

- Don’t assume ‘no data’ means ‘safe.’ It just means no good studies exist yet.

What to Do When the Label Is Unclear

Some labels still have gaps. A 2023 Government Accountability Office report found that 63% of psychiatric drug labels didn’t specify which trimester carried the highest risk-even though timing matters a lot. So what do you do? Use trusted databases. TERIS (Teratogen Information System) and MotherToBaby are free, evidence-based resources updated daily. Pharmacists use them. OB-GYNs use them. If you’re unsure, call MotherToBaby at 1-866-626-6847. They’ll walk you through the label and explain what it means for your situation.Why This Matters More Than Ever

Since the new labeling started, pregnancy exposure registries have grown by 400%. In 2022, over 25,000 pregnant women were tracked across 47 registries. That’s data. Real data. And it’s changing how we treat chronic conditions like epilepsy, depression, and diabetes during pregnancy. Women aren’t being told to stop their meds. They’re being given real numbers so they can decide with their doctors. A 2022 Medscape poll showed 73% of perinatal specialists prefer the new format. Why? Because it lets them say: ‘Your risk of a seizure if you stop this drug is 40%. The risk of a birth defect from this drug is 4%. We can manage both.’ That’s not possible with a letter.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Don’t confuse relative risk with absolute risk. A ‘2-fold increase’ sounds scary-but if the background risk is 1%, doubling it means 2%. That’s still low.

- Don’t assume ‘no data’ = ‘safe.’ It just means we don’t have good studies yet. Use a registry or expert resource.

- Don’t skip the Lactation section. Many drugs are safe in pregnancy but not in breastfeeding-or vice versa.

- Don’t rely on old websites or apps that still use letter categories. They’re outdated.

What’s Next?

The FDA is working on visual icons to go with the text-like a tiny baby with a caution sign. They’re also pushing for more diverse data in registries. Right now, only 15% of participants are Black or Hispanic, even though they make up 30% of U.S. pregnancies. That’s a gap. But progress is real. By 2025, the FDA plans to have 100% of pregnancy-related drug labels updated. That means every prescription you get from now on will give you real, usable info-not a letter you have to guess at.Are pregnancy letter categories (A, B, C, D, X) still used on drug labels?

No. The FDA eliminated the letter categories in 2015 under the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR). All drugs approved after June 30, 2015, use narrative labeling. Drugs approved before that date were required to update their labels by December 2020. If you see a letter on a label today, it’s either outdated or incorrectly printed.

Is it safe to take medication while breastfeeding?

Many medications are safe during breastfeeding. The Lactation section of the drug label tells you how much of the drug enters breast milk (usually as a percentage of the mother’s dose). If infant exposure is under 10%, it’s generally considered low risk. Always check for specific warnings like ‘drowsiness’ or ‘poor feeding’ in the baby. When in doubt, consult MotherToBaby or your pharmacist.

What does ‘background risk’ mean on a drug label?

Background risk is the chance of a birth defect or miscarriage in any pregnancy, regardless of medication use. In the U.S., it’s about 3% for major birth defects and 10-20% for miscarriage. Drug labels compare their risk to this baseline. For example, if a label says ‘1.5-fold increased risk,’ it means the risk goes from 3% to 4.5%-not from 0% to 1.5%.

Why do some drug labels say ‘no data available’ for pregnancy?

It means there aren’t enough well-designed studies in pregnant women. That doesn’t mean the drug is dangerous-it just means we don’t have clear evidence. In these cases, doctors rely on animal studies, case reports, or registries. If you’re pregnant and need the drug, your provider may recommend joining a pregnancy exposure registry to help build better data.

Can I trust the FDA’s new labeling system?

Yes. The new system is based on real data from thousands of pregnancies and breastfeeding cases. It was developed after years of research showing the old letter system caused confusion and misinterpretation. While it requires more reading, it gives you real numbers and context-not vague categories. Over 78% of U.S. prescription drugs now use this format, and major medical organizations like ACOG and the FDA endorse it.

What should I do if my doctor prescribes a drug with unclear pregnancy labeling?

Ask your doctor to check the official FDA label using the Drugs@FDA website or the PLLR Navigator app. You can also call MotherToBaby at 1-866-626-6847 for free, expert advice. Never stop a medication for a chronic condition without talking to your provider-untreated conditions like epilepsy or depression often carry higher risks than the medication itself.

jamie sigler

December 1, 2025 AT 08:43This is such a waste of time. Why can't they just put a simple A, B, C back? I don't wanna read paragraphs just to figure out if my antidepressant will turn my baby into a lizard. 🤡

Bernie Terrien

December 2, 2025 AT 17:54The old system was a dumpster fire. C meant ‘probably fine unless you’re a witch.’ Now we get numbers. Real ones. No more guessing games. FDA finally stopped coddling lazy doctors.

Subhash Singh

December 2, 2025 AT 21:09It is indeed a commendable advancement in pharmacovigilance and patient-centered communication. The transition from categorical labeling to narrative risk quantification aligns with evidence-based medicine principles and enhances informed decision-making. The inclusion of clinical considerations and data transparency represents a paradigm shift in regulatory labeling.

Geoff Heredia

December 4, 2025 AT 10:29They say it's 'transparency' but I bet Big Pharma pushed this so they could bury the real risks in 12 paragraphs of legalese. Who the hell reads all this? And why is there no icon yet? This feels like a distraction tactic. I'm calling the FDA right now.

Tina Dinh

December 4, 2025 AT 13:06YESSSS!! 🙌 Finally someone tells the truth about meds and babies! I was so scared to take my anxiety meds during pregnancy, but now I get it - 4.5% risk vs 3%? That’s not scary, that’s just life. Thank you for this 💕

Peter Lubem Ause

December 5, 2025 AT 17:59This is one of the most important updates in modern obstetric pharmacology. The shift from vague letter grades to data-driven narratives empowers patients and clinicians alike. The lactation section, in particular, is revolutionary - quantifying infant exposure as a percentage of maternal dose transforms clinical reasoning. I’ve used this in my practice for three years now, and the reduction in patient anxiety and unnecessary medication discontinuation has been profound. We must also push for broader demographic inclusion in registries - equity in data is not optional.

linda wood

December 6, 2025 AT 13:33Wow. So now instead of one letter, I have to read a novel written by a bureaucrat who thinks I have a PhD in pharmacokinetics? 😏 At least the ‘no data’ part is honest - it just means nobody bothered to study it on actual humans. Thanks, science.

LINDA PUSPITASARI

December 6, 2025 AT 17:22Just read the new label for my SSRIs and cried a little - it actually said ‘infant exposure 6%’ and ‘rare drowsiness’ not ‘DO NOT BREASTFEED’ 😭 I’ve been terrified for months. This system is a gift. MotherToBaby saved me. Also - if you’re scared, call them. They’re angels. 🤍

Joy Aniekwe

December 8, 2025 AT 02:28Let me get this straight - you replaced a simple system that everyone understood with one that requires a degree in statistics and a Google search? And you call this progress? I’ve seen women panic over ‘1.5-fold increase’ when it’s literally 0.03% extra risk. This isn’t transparency. It’s performance art.

Latika Gupta

December 8, 2025 AT 21:23Why is the lactation section so detailed but the fetal development part still vague? If the drug crosses the placenta, why aren't we getting more on organogenesis timing? The FDA is good, but this feels like half a solution. Someone needs to push for trimester-specific risk stratification - not just ‘first trimester bad’ but ‘week 7-12 = critical window.’

Sullivan Lauer

December 9, 2025 AT 22:31I’m a nurse in OB-GYN and let me tell you - this system changed my life. I used to get 20 panicked calls a day because someone saw ‘Category C’ and thought their baby was doomed. Now? I say ‘Look at the risk summary - baseline is 3%, this raises it to 4.5%. That’s like the risk of being hit by lightning twice in your life.’ And they breathe. They actually breathe. I’ve had women cry because they finally felt heard. This isn’t just a label update - it’s a mental health win. And yes, I still tell them to call MotherToBaby. Because sometimes you need to hear it from someone who’s been there. 🫂