Drug-Gene Interaction Checker

Understand Your Medication Risks

Select a common medication to see how genetic factors might affect your response and potential side effect risks.

Some people take a common medication and feel fine. Others get sick-sometimes dangerously so-on the same dose. It’s not always about dosage, allergies, or lifestyle. Often, it’s written in their DNA.

Why Your Genes Decide How You React to Medication

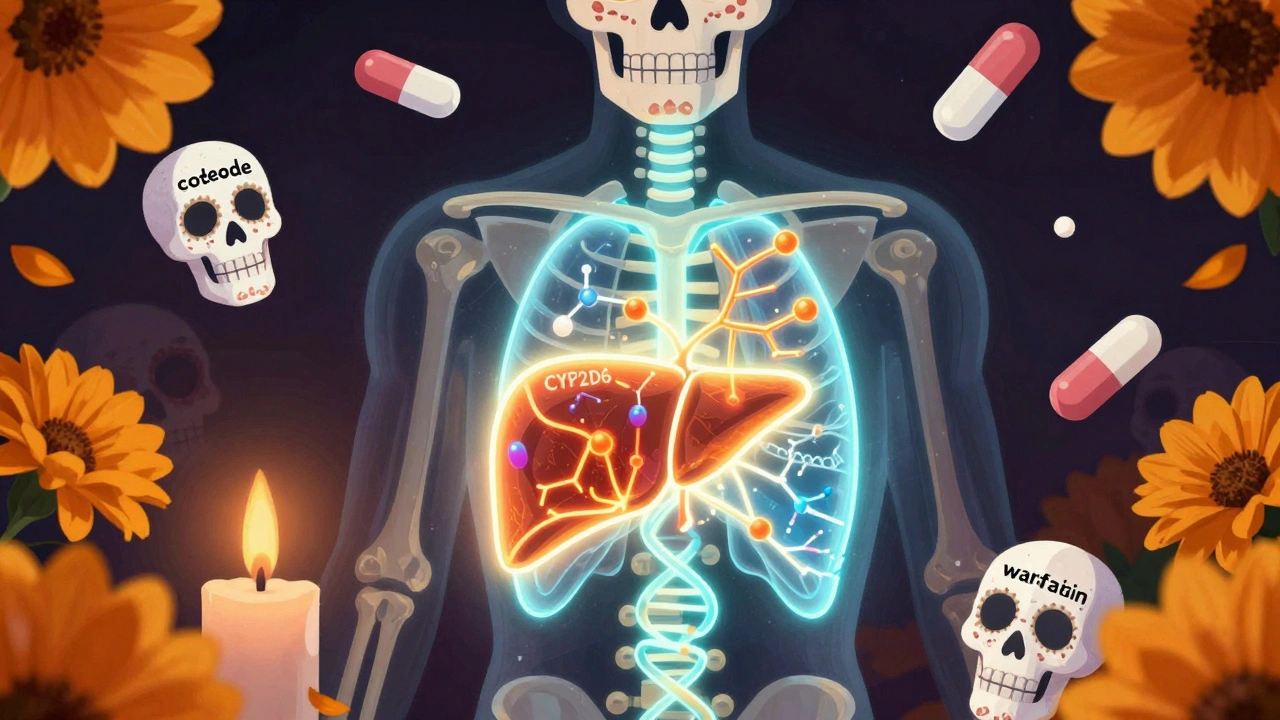

Your body doesn’t process drugs the same way everyone else’s does. That’s not a flaw-it’s biology. The differences come from tiny variations in your genes, called polymorphisms, that change how enzymes break down medicines, how transporters move them through your body, and how your cells respond to them. These variations can turn a safe drug into a dangerous one-or make it completely ineffective.Take CYP2D6, a liver enzyme responsible for processing over 25% of commonly prescribed drugs, including antidepressants, painkillers like codeine, and tamoxifen for breast cancer. Some people have a version of this gene that makes them ultrarapid metabolizers. They turn codeine into morphine so fast that even a normal dose can cause life-threatening breathing problems, especially in babies exposed through breast milk. Others are poor metabolizers. Their bodies barely touch the drug, so it doesn’t work at all. In tamoxifen users, poor metabolizers get fewer side effects like hot flashes-but they also get less protection against cancer recurrence.

Genes That Can Trigger Life-Threatening Reactions

Not all side effects are mild nausea or dizziness. Some are catastrophic-and genetics can predict them with startling accuracy.The HLA-B*15:02 gene variant is a prime example. Carriers of this variant, mostly of Asian descent, face a 100 to 150 times higher risk of developing Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) or Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN) if they take carbamazepine or phenytoin, two common seizure medications. These conditions cause the skin to blister and peel off, often leading to hospitalization, organ failure, or death. Because of this, the FDA now requires doctors to test for HLA-B*15:02 before prescribing these drugs to patients with ancestry from Southeast Asia. The test isn’t perfect-only about 5% of people who carry the gene will actually develop SJS-but if you don’t have the gene, your risk drops to near zero. That’s the power of a strong negative predictive value.

Another high-risk gene is CYP2C9*3. People with this variant who take phenytoin are 3.5 times more likely to suffer severe skin reactions. Warfarin, a blood thinner, is even more genetically sensitive. Two genes-VKORC1 and CYP2C9-explain up to 45% of why some people need just 1 mg a day while others need 10 mg. Too much warfarin causes dangerous bleeding; too little doesn’t prevent clots. Without genetic testing, doctors often spend weeks adjusting doses through trial and error.

Cardiac Risks Hidden in Your DNA

Some drug side effects strike the heart-and genetics can reveal who’s at risk before the first pill is taken.Up to 5% of people who develop drug-induced torsades de pointes, a dangerous heart rhythm, have hidden mutations linked to Long QT Syndrome. These mutations affect genes like KCNH2, KCNQ1, and SCN5A, which control the heart’s electrical signals. Even if someone has never had heart problems, taking certain antibiotics, antipsychotics, or anti-nausea drugs can trigger a fatal arrhythmia if they carry these variants.

Even rarer but just as telling is the ANK2 gene variant. Found in 2.2% of patients with extreme QT prolongation from medications, this variant disrupts heart cell function in ways that mimic inherited heart conditions. Doctors rarely test for it-but when they do, it explains why some patients react badly to drugs that are safe for others.

Why Some Side Effects Are Easier to Predict Than Others

Not all side effects are created equal when it comes to genetic prediction. A 2024 study in PLOS Genetics found that cardiovascular side effects-like irregular heartbeat, high blood pressure, or chest pain-are the most predictable. When a drug’s target gene is already known to influence heart function, the risk of side effects jumps by nearly 30% in genetically susceptible people.But look at gastrointestinal side effects-nausea, diarrhea, stomach pain. These are common, but genetics explains less than 10% of why they happen. That’s because they’re often caused by direct irritation, gut bacteria changes, or even psychological factors, not gene-driven metabolism.

This matters because it tells us where to focus. Instead of testing everyone for every side effect, doctors should target high-risk, high-impact reactions. For example, testing for HLA-B*15:02 before prescribing carbamazepine saves lives. Testing for CYP2D6 status before giving codeine to breastfeeding mothers prevents infant deaths. These aren’t theoretical-they’re proven.

What’s Being Done-and What’s Still Missing

The FDA keeps a growing list of 128 gene-drug pairs with clear clinical guidance. That includes drugs like clopidogrel, voriconazole, and abacavir. For abacavir, an HIV medication, the HLA-B*57:01 test is so reliable that if you test negative, you’re virtually guaranteed not to have a dangerous allergic reaction. But here’s the catch: only 5-10% of people who test positive actually develop the reaction. So while the test prevents harm, it also means many people are denied a useful drug based on a genetic flag that doesn’t always mean danger.Meanwhile, organizations like the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) have created 24 official guidelines to help doctors use this data. But here’s the reality: only 10-15% of doctors routinely use pharmacogenetic testing. Why? Many say they don’t know how to interpret the results. A 2023 survey found 68.5% of physicians felt untrained. Others say the results come too late-after a patient already had a bad reaction.

Testing Is Available-But It’s Not Easy

You can get a pharmacogenetic test today. Companies like Color Genomics and OneOme offer panels that check 10-20 key genes for around $250-$500. Some insurance plans cover it, especially for cancer or psychiatric treatment. Medicare, however, only pays for testing on 7 of the 128 FDA-recommended gene-drug pairs.Even when the test is done, hospitals often can’t use the results. Only 37% of U.S. hospitals have electronic systems that alert doctors when a patient’s genetics conflict with a prescribed drug. At Vanderbilt’s PREDICT program, where testing is built into the EHR, doctors changed prescriptions for 12.3% of patients based on genetic results. Most of those changes avoided side effects.

But there’s a gap between research and real-world care. A patient on Reddit shared that her doctor waited three weeks for CYP2D6 results before starting tamoxifen. She was lucky-her sister had terrible nausea. But not everyone has access to that kind of care. In rural clinics, or in practices without genetic specialists, testing is still a luxury.

The Future: More Testing, Better Tools

The future is moving toward preemptive testing-testing your genes once, early in life, and using that data for every prescription you ever get. The All of Us Research Program has already returned pharmacogenetic results to over 200,000 people. Nearly half carry at least one actionable variant.New tools are emerging too. A 2024 study in Nature Medicine used a 15-gene score to predict statin-induced muscle pain with 82% accuracy-far better than testing just one gene (SLCO1B1). This is the shift from single-gene checks to polygenic risk scores, which look at dozens of small genetic signals together.

By 2030, experts predict 40% of all prescription drugs will come with genetic testing recommendations. The FDA is preparing for this. Their new draft guidelines could require genetic testing for 35+ drugs by 2027.

But progress isn’t equal. Less than 5% of pharmacogenetic studies include enough people of African ancestry-even though African populations have the highest genetic diversity. That means tests developed mostly on white European populations may miss key variants in other groups, putting them at risk.

What You Can Do Now

If you’ve had unexpected side effects from medications, or if your family has a history of bad reactions, talk to your doctor about pharmacogenetic testing. It’s not magic-but it’s one of the most powerful tools we have to make medicine safer.Ask if your provider uses clinical decision support tools that flag gene-drug conflicts. If they don’t, ask if they’re familiar with CPIC guidelines. If you’re on a long-term medication like warfarin, tamoxifen, or an antidepressant, genetic testing could prevent months-or years-of trial and error.

And if you’ve had a reaction you can’t explain? Your genes might hold the answer. You’re not broken. You’re just genetically different-and that’s something medicine is finally learning to respect.

Can genetic testing prevent all drug side effects?

No. Genetic testing can only predict side effects caused by inherited differences in drug metabolism, transport, or target response. It won’t help with allergic reactions, overdoses, drug interactions, or side effects caused by lifestyle or other medical conditions. But for certain high-risk reactions-like those tied to HLA-B*15:02 or CYP2D6-it can prevent serious harm.

Which drugs have the strongest genetic warnings?

Drugs with the clearest genetic links include carbamazepine (HLA-B*15:02), warfarin (CYP2C9 and VKORC1), codeine (CYP2D6), abacavir (HLA-B*57:01), and clopidogrel (CYP2C19). The FDA requires genetic testing or warnings for these drugs in their labeling. Tamoxifen and statins also have strong genetic associations with effectiveness and side effects.

Is pharmacogenetic testing covered by insurance?

It depends. Medicare covers testing for only 7 of the 128 FDA-recommended gene-drug pairs. Private insurers vary widely-many cover it for cancer, psychiatric, or pain management drugs if deemed medically necessary. Out-of-pocket costs range from $250 to $500. Some employers and health systems offer testing as part of preventive care programs.

Can I get tested without a doctor’s order?

Yes-companies like 23andMe and Color Genomics sell direct-to-consumer pharmacogenetic panels. But be cautious. The FDA has issued warning letters to companies that overstate the clinical usefulness of their results. A raw genetic report without medical interpretation can lead to wrong decisions. Always discuss results with a doctor or pharmacist trained in pharmacogenomics.

Why isn’t genetic testing used more widely in clinics?

Three main barriers: lack of clinician training, poor integration with electronic health records, and inconsistent insurance coverage. Many doctors don’t know how to read the reports. Hospitals lack systems to alert them when a genetic conflict exists. And without reimbursement, testing often doesn’t get ordered. But pilot programs like Mayo Clinic’s RIGHT Protocol show that with the right infrastructure, testing reduces hospitalizations by 23%.

Declan O Reilly

December 2, 2025 AT 22:02Man, I had no idea my body was basically a glitchy app running on outdated firmware. Took codeine for a toothache once and felt like I was being smothered by a pillow made of angels. Turns out I’m an ultrarapid metabolizer. My doctor just shrugged and said ‘we’ll try something else.’ No test, no warning-just luck I didn’t end up in the ICU.

Genetics isn’t sci-fi anymore. It’s the difference between surviving your meds and becoming a cautionary tale.

Conor Forde

December 4, 2025 AT 17:50Oh here we go again-the ‘your DNA is your destiny’ sermon. Let me guess, next you’ll tell me my love of nachos is coded in my SNPs? The HLA-B*15:02 thing? Sure. But let’s not pretend this is some golden ticket. Most people don’t even know what a polymorphism is. And the fact that 95% of the studies are on white folks? That’s not precision medicine-that’s colonial medicine with a lab coat.

Also, ‘talk to your doctor’? My GP still thinks ‘pharmacogenomics’ is a new type of yoga.

patrick sui

December 6, 2025 AT 00:52Big picture alert: We’re moving from reactive medicine to predictive medicine-and it’s about time. 🧬💡

Think of it like a car’s diagnostic code. If your engine light comes on, you don’t just guess what’s wrong-you plug in the scanner. Why should our bodies be any different?

CPIC guidelines exist. The data is solid. The tech is affordable. The gap? It’s not science-it’s systems. EHRs need to be built to scream ‘GENETIC CONFLICT!’ before the script is printed. Until then, we’re just putting bandaids on a leaking dam.

Also-yes, diversity in genomics is CRITICAL. African genomes are the most diverse on Earth. Ignoring them isn’t just unethical-it’s bad science. We’re literally missing the blueprint of humanity.

Priyam Tomar

December 7, 2025 AT 19:48Everyone’s acting like this is new. My uncle in Delhi got sick on phenytoin in 1998. They didn’t have genetic tests then, but they knew-because his cousin died the same way. This isn’t rocket science. It’s common sense wrapped in a DNA helix.

And no, 23andMe doesn’t count. You don’t need a $500 test to know your family has a history of bad reactions. Just ask your mom. Or your aunt. Or the ghost of your great-grandpa who died after ‘a little aspirin.’

Stop overcomplicating it. Genetics isn’t magic. It’s just biology with better labels.

Jack Arscott

December 9, 2025 AT 18:34So… if I have the HLA-B*15:02 variant, does that mean I can’t ever have a seizure again? 😅 Just asking for a friend. (It’s me. I’m the friend.)

Michelle Smyth

December 10, 2025 AT 16:21How quaint. We’ve reduced human physiology to a spreadsheet of SNPs and called it ‘progress.’ How convenient-now we can blame the patient’s DNA when the doctor doesn’t bother to listen.

Let’s be honest: the real problem isn’t the lack of testing-it’s the lack of empathy. You can sequence every base pair, but if your physician still thinks ‘nausea’ is just ‘bad attitude,’ you’re not saving lives-you’re just collecting data for a TED Talk.

Patrick Smyth

December 11, 2025 AT 12:27My daughter took lamotrigine and broke out in blisters. We didn’t know about HLA-B*15:02. We didn’t even know what it was. She spent 17 days in the hospital. Her skin peeled like old wallpaper. She cried every night.

Now I test every single person in my family. Every. Single. One.

They think I’m paranoid. I think they’re idiots.

And yes-I’ve yelled at my GP. Twice. He still doesn’t know what CPIC is.

Linda Migdal

December 13, 2025 AT 03:44Let’s not forget: America leads in this. We’ve got the FDA, the NIH, the PREDICT program-none of this happens without U.S. investment. Other countries? They’re still arguing over whether to wear masks. We’re rewriting the rules of medicine.

Stop acting like this is some global conspiracy. It’s American innovation. Own it.

Tommy Walton

December 14, 2025 AT 10:03Genetics isn’t destiny. It’s a heads-up. 🚨

Test early. Stay informed. Don’t be the guy who blames the pill when it’s his SNPs doing the talking.

Also, if your doctor says ‘we’ll try it and see’-find a new one.